Market update - Geopolitics and Ukraine

Military conflicts and other global shocks will typically have a negative short term impact on financial markets, most notably on riskier assets such as equities. The start of a conflict between Russia and Ukraine has been no exception, with a short term fall being experienced by equity markets, and some support for safe-haven assets such as bonds and gold. Beyond the initial shock, how do markets usually behave in the aftermath of these events, and what are the best ways to deal with the short term increases in volatility?

Background

On the 24th February, after weeks of speculation, Russian military forces launched a multi-front attack on neighbouring Ukraine. The conflict can be traced back to 2014, when Russia annexed the Crimean territory, following a disputed referendum in the region that supported independence, and eventual incorporation into the Russian Federation. The region, like much of Eastern Ukraine, has a large ethnic Russian population. Figure 1 below outlines this divide:

Figure 1: Russian speaking populations in the Ukraine

Source: Australian Broadcasting Corporation

The latest conflict is centred on the Donbas region, which consists of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions on the above map. Russian incursions have also been made to the North via Belarus and the South into Odesa.

The stated motives of the invasion, given by Russian President Vladimir Putin, are to protect the populations of the Donbas region from persecution by the Ukrainian government. Beyond this, others have proposed that the real reasons are more complex, and involve countering the influence of NATO and territorial expansion.

To date, the NATO member states have not been drawn into the conflict, and there are no plans to send combat troops into Ukraine. A wide range of sanctions have been announced, targeting the financial and energy sectors and key government personnel.

Impact on Markets

Geopolitical shocks such as this usually lead to a ‘risk-off’ move in markets. Typically, growth focussed assets, such as equities will be weaker, but more defensive assets, such as bonds and gold often see price increases. As at the end of February, this is what largely played out.

Global equities had already been weak heading into the conflict, as expectations of interest rate increases in the coming months have seen most equity markets lower for the year so far.

Commodity prices have generally increased. Given the importance of Russia to global energy markets (the 3rd largest oil producer and 2nd largest gas producer), energy prices have headed higher, with oil trading around $US100 per barrel. Gold prices have increased as a part of a flight to safety. The prices of a number of other industrial metals where Russia is a key supplier, such as nickel, have also increased. The area is also a key grain producer, and there is upward pressure on some agricultural commodity prices.

Bond prices, which have been falling in recent months on market expectations that interest rates will rise in the coming months, have recently recorded some modest gains. Bond prices often move in the opposite direction to equity prices at times of distress.

Beyond the moves on financial markets, the key impact to the real economy is likely to be further inflationary pressures that flow from higher energy and commodity prices. Apart from this, given the reluctance of NATO to put combat troops into the area, the ongoing impact to the global economy could be modest.

Long term considerations

The fear and uncertainty caused by these events usually leads to modest drawdown in financial markets. But how long does this persist?

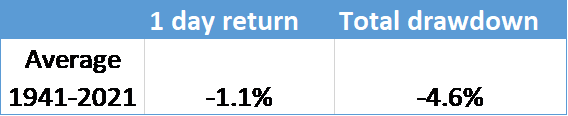

US financial services firm LPL Financial has examined the impact of 22 previous conflicts or terrorist events on the US stock market index (S&P 500) since the Second World War. Historically the one-day move on the event has been an average negative return of 1.1%, and the total drawdown (the lowest point before the recovery) has been -4.6%, as shown in Table 1 below. Some events have had a materially larger impact. As of the 28th of February, the largest drawdown in the S&P 500 since the beginning of the conflict has been 1.9%.

Table 1: Short term impact of Geopolitical Shocks to the S&P 500

Source: LPL Financial

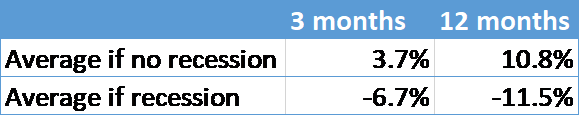

The same analysis has also considered what has happened to market returns in the 12 months following a major geopolitical event or market shock. This found that if the shock was accompanied by a recession, the average market return 3 months later was -6.7%, and 12 months later was -11.5%. However, if it was not a recession, the market was 3.7% higher after 3 months and 10.8% higher after 12 months. Table 2 summarises the findings:

Table 2: Medium term returns for the S&P 500 following market shocks

Source: LPL Financial

Combined, this suggests that the impact from geopolitical shocks is often quite short, and other broader economic factors could have a more material impact.

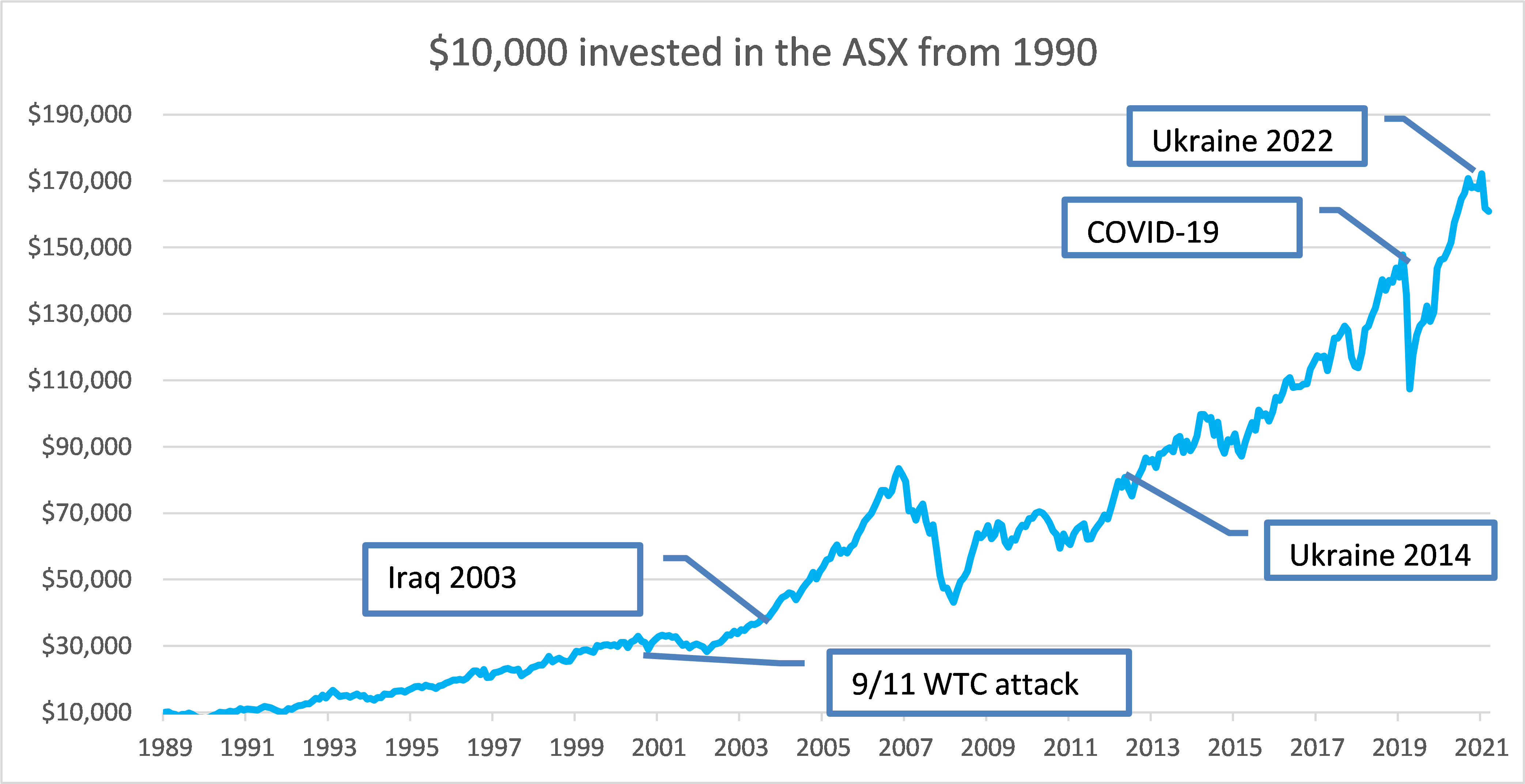

Looking at a long term chart of the Australian market (ASX 200) also puts this into perspective. Since 1990, the largest shocks to the market have been from the Global Financial Crisis which began in 2007, and the COVID-19 Pandemic from 2020. The September 11 terrorist attacks, the US invasion of Iraq, and the previous Russian annexation of Crimea appear as short term blips:

Chart 1: Long term ASX returns to 28 Feb 2022

Source: Fiducian

Conclusion

The current conflict may still be in the early stages, and there could be considerable uncertainty in financial markets until a resolution is clear. Until this happens, riskier assets may still experience higher than average volatility.

Looking back over recent history, similar geopolitical shocks (albeit generally of a smaller scale) have proved to only have a short term impact on stock market returns, especially if there is no accompanying recession.

It is important for investors to maintain an appropriate time horizon, as over longer term periods, equities have generated strong returns, despite short term volatility.

These events also highlight the importance of a diversified portfolio. As equity markets have fallen, other assets, such as bonds and commodities, have recorded gains. This not only reduces the variability of portfolio values, but gives investors the opportunity to redeploy capital back into the market at an opportune time.

Disclaimer

Issued by Fiducian Investment Management Services Limited (ABN 28 602 441 814, AFSL 468211) (‘Fiducian’). The views and opinions contained herein are those of the authors as at the date of publication and are subject to change due to market and other conditions. The information in this document is given in good faith and we believe it to be reliable and accurate at the date of publication. Fiducian and its officers give no warranty as to the reliability or accuracy of any information and accept no responsibility for errors or omissions. The information is provided for general information only and is not personal advice. It does not have regard to any investor objectives, financial situation or needs. It does not purport to be advice and should not be relied on as such. Investment and tax advice should be sought in respect of individual circumstances. Except to the extent that it cannot be excluded, Fiducian accepts no liability for any loss or damage suffered by anyone who has acted on any information in this document. Past performance is not indicative of future performance and we do not guarantee any particular performance or any specific rate of return.